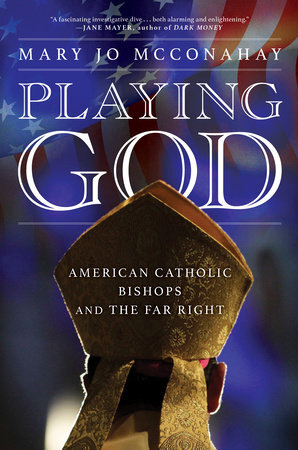

Playing God: American Catholic Bishops and the Far-Right

By Mary Jo McConahay (Melville House, 2023)

Some conservative Catholics like to disparage social changes. They say these changes are the work of worldly and sinful forces antithetical to the church’s values. Take a look, for example, at the language used on the website of a conservative Catholic organization, the Napa Institute: “a culture that is ignorant of [God’s] ways and hostile toward [the] Church,” “a confusing and changing world” which is “stridently promoting” a movement that’s “radically at odds with the Catholic understanding of the human person.” The website also refers to “the scandal and corruption of Catholics who do not align with or serve our mission . . . to bring light back into society.”

The irony is that elite donors (and the wealth they control) are enabling contemporary conservative causes in the United States. Mary Jo McConahay’s Playing God: American Catholic Bishops and the Far-Right (Melville House, 2023) examines the growing entanglement of the U.S. Catholic hierarchy with right-wing organizations that seek to weaken or overturn democratic institutions in the name of religious liberty. They want to remake the country into a nation of laissez-faire capitalism and conservative cultural ideals.

McConahay offers a dizzying array of players and connections that contribute to this scenario. In addition to the Napa Institute, she points to other conservative organizations, such as the Beckett Fund for Religious Liberty; news media like EWTN; the Busch School of Business and Economics at Catholic University of America (founded by the U.S. bishops, it received $10 million from billionaire Charles Koch in 2017); and Catholic influencer Leonard Leo.

Many Catholics may not be familiar with Leo. But he controls a network of nonprofits and is best known for having quietly reshaped the Supreme Court by advancing conservative nominees and helping to quash others. According to the Washington Post, Leo raised more than $250 million in donations between 2014 and 2017, some of which was used to derail the nomination of Merrick Garland, then-President Obama’s Supreme Court pick in 2016, and greenlight the appointments of Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Comey Barrett. Since then, a single businessman donated all the shares of his company, worth $1.6 billion, to Leo’s Marble Freedom Trust, which was then sold for cash, making Leo the ultimate banker of right-wing causes like bans on abortion and defending the right of Catholic organizations to discriminate against LGBTQ people.

A key issue McConahay reveals is the “dark” money flowing through far-right Catholic networks, meaning organizations that manage these funds are not obligated to identify their sources so long as they are nonprofit. These groups are using “politics and the courts to install their version of Christendom in the United States” (McConahay, 107), and they often disperse money with a political agenda in mind. The National Catholic Reporter and the Daily Beast recently reported that in 2020, DonorsTrust, another conservative dark-money fund, channeled funds to several traditionalist Catholic parishes and dioceses, a few religious liberty law firms and think tanks, various Catholic colleges and organizations, and one student antiabortion group. It also gave millions of dollars to organizations associated with both white supremacy and conspiracy theories about the 2020 election.

Most Catholics know what traditionalist discontent usually looks like: disapproval of Vatican II and Pope Francis, as well as a rejection of contemporary culture, especially feminism, reproductive rights, and “political identity movements.” Many ultraconservative objectives—capitalism without constraint, deregulation of industry, removal of the social safety net, and the “debunking” of climate change—seem inherently un-Catholic. But other conservative causes are even more insidious, such as supporting white supremacy or insisting that Donald Trump had the right to overturn the 2020 election and invalidate 81 million votes for Joe Biden. Intentions like these threaten our nation’s very foundation—the ideals that hold and keep it together—and should not be tolerated.

The average Catholic, confronted with these far-right trends in churches, may find workarounds by changing parishes, or vetting the organizations to which they donate money. However, right-wing discontent in the wider political sphere is complicated and dangerous. The existence of these more dangerous currents may elude the average parishioner. Not knowing the source of funding for different programs makes it nearly impossible tor many Catholic parishioners to discern which organizations’ objectives align with their own.

As McConahay writes, Pope Francis is aware that some conservative goals violate the protection of human life, a bulwark of Catholicism. In his 2015 encyclical Laudato Si (On care for our common home) Francis proclaimed “the holiness and interconnectedness of all creation,” and included a powerful indictment of “unrestrained capitalism” (McConahay, 195). McConahay notes that U.S. bishops, wary of being associated with anything “environmental,” refused to praise the encyclical. The most popular explanation for American bishops’ silence on environmental issues is that they have made abortion their number-one priority.

So what, if any, is the solution to the problems McConahay addresses?

Playing God suggests the money flowing through the Catholic ultraright network could be dammed if, for example, the bishops were to produce something along the lines of Economic Justice for All. This 1986 pastoral letter prioritized Catholic social teaching over free markets and was aimed squarely at the Reagan administration’s economic policies.

Playing God also includes a chapter (“Our Common Home”) that provides additional guidelines for ordinary Catholics. One way of confronting complacency regarding climate change, for example, might be to seize the reins in your own parish: Hold an information night, plant a parish garden, organize an outdoor cleanup, or lobby government representatives (activities parishioners at St. Ignatius parish in San Francisco have all undertaken).

One Catholic featured in this section, Betsy Reifsnider, former environmental justice director at Catholic Charities in Stockton, admits that Catholics stepping forward on this issue are often “operating in silos,” and that many Catholics do not know Laudato Si exists or that there could be such a thing as “ecological sin.” A small but growing network of Catholics are trying to change that, however, and they are ready to welcome others and share ideas, Father Emmett Farrell of San Diego told McConahay. Farrell is part of Creation Care Ministry, which speaks to parishes about Catholicism and the environment.

When parishioners take a stand for prioritizing Catholic social teaching over finances, they can also open discussions about money—where it comes from, where it goes, and why talking about it is important. When people invested in positive change raise their voices, they are less likely to be dismissed than dissenters who don’t offer any practical solutions.

After hearing revelations of clerical sexual abuse—and the church’s cover-up—Catholics have become accustomed to asking questions and not getting satisfactory answers. When answers do come, it often turns out that the lone wolf who spoke out early and was ignored was on the right track. For many Catholics, however, it’s sometimes easier to have a head-in-the-sand attitude. Most Catholics have not even begun to ask about the money swirling around the ultraconservative causes U.S bishops tacitly support.

Now would be a good time to start asking questions.

Image: Unsplash/Giorgio Travato

Add comment