The idea of equity has become a hot topic in American society. According to the National Association of Colleges and Employers, a professional association for college career service centers, “equality means providing the same to all, [but] equity means recognizing that we do not all start from the same place and must acknowledge and make adjustments to imbalances.” Likewise, McGill University states, “Equity, unlike the notion of equality, is not about sameness of treatment. Equity denotes fairness and justice in process and in results.”

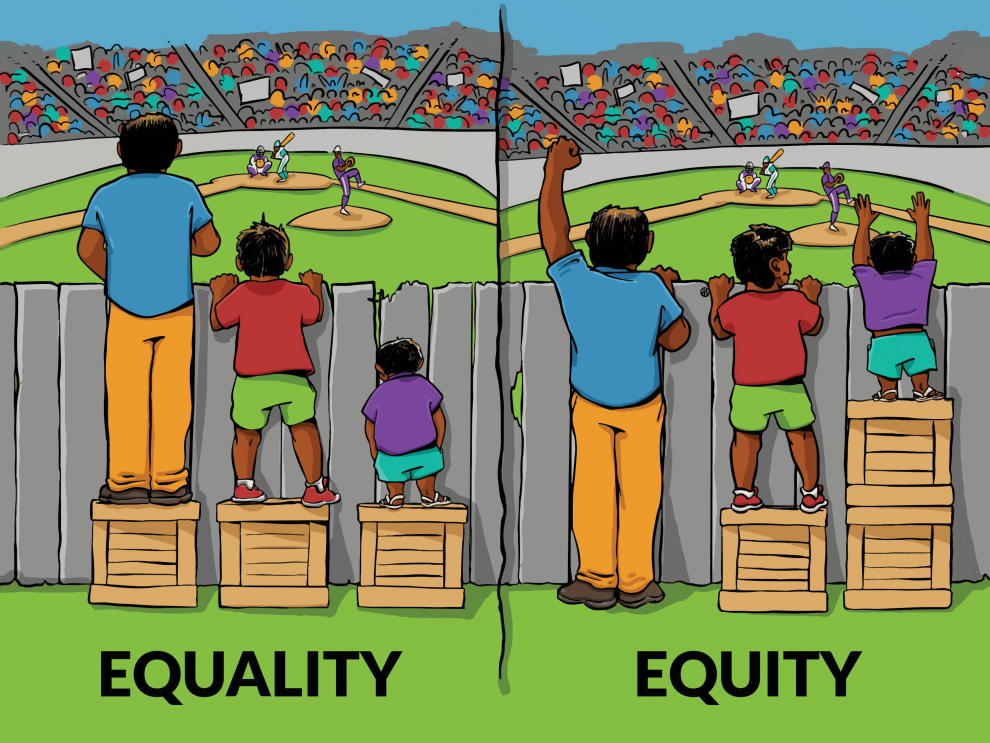

Both of these websites use a common illustration of equity: three people of different heights trying to look over a fence at a game. If you give each person a box to stand on (“equality”), then the shortest person still cannot see over the fence. But the tallest person doesn’t need the box at all. Equity means giving two boxes to the shortest person and no box to the tallest, because then everyone can see the game.

While there is no direct official Catholic teaching on equity, there are surely reasons why Catholics should think in equity terms and share the boxes. Modern Catholic social teaching formulates the principle of the preferential option for the poor. The church’s Compendium of Social Doctrine states: “the poor, the marginalized and in all cases those whose living conditions interfere with their proper growth should be the focus of particular concern.”

While this concern sometimes goes under the notion of “charity,” a form of Christian love, the Compendium insists that it is also a matter of justice. The text quotes sixth-century St. Gregory the Great: When we support the poor, “more than performing works of mercy, we are paying a debt of justice.”

Why is this preferential option fair? Because of St. Pope Paul VI’s idea that “every life is a vocation.” When I teach this idea in my classes, I use the example of parents who rightly want each of their children not just to survive but also to flourish in their own unique way. Good parents give each child what they need to achieve their full potential—and, of course, this is not strictly equal.

On a social level, it is now widely recognized that schools and workplaces need to accommodate people with disabilities. Making accommodations is more than just giving some people an extra box to stand on; we recognize that we need to design buildings and other public spaces so that people with different abilities do not need the “extra box” but can get around the space easily.

However, determining equity is not always as easy as using boxes to overcome physical differences. Obviously humans are not all the same height; as a tall person, I recognize the indirect benefits that come from being able to see above the crowd. But there’s no reasonable way to make everyone the same height. Inherent in the idea that every life is a vocation is that we all have different talents and abilities. Equity cannot be a matter of erasing those differences.

Thus, in seeking justice, we often overlook more complicated situational factors. For example, the recent Supreme Court decision rejecting race-conscious admissions policies at elite universities is controversial in part because we have developed a mentality that everyone should go to college and a ranked hierarchy of “elite” universities, with huge impacts on one’s life opportunities. What goes unheard in these debates is that, because of this universal expectation, the rigid hierarchy of schools, and the fixed limits on enrollment at elite schools, there aren’t enough boxes to go around.

A further difficulty is the debate between equality of opportunity versus equality of outcome. Even the opportunity to attend Harvard doesn’t guarantee outcomes. The box example also obscures this difficulty, because the outcome (seeing over the fence) is also the opportunity. But many other situations are vastly more complicated. The achievement of one’s vocation is in part due to one’s own efforts. In the same passage about vocation, St. Pope Paul VI writes that each person is “aided, or sometimes impeded, by those who educate him and those with whom he lives, but each one remains, whatever be these influences affecting him, the principal agent of his own success or failure.” Even so, the preferential option for the poor surely should focus us on providing all necessary help.

Finally, the equity discussion gets even more complicated when we move from individual outcomes (of which Paul VI is speaking) to equity of group outcomes. A relatively trivial example: Psychologists Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt discuss how men’s crew is not a university-funded sport at the University of Virginia, but women’s crew is, because a federal program mandates that the numbers of official student athletes by gender must match the overall composition of the student body. Or a more serious example: A recent story highlighted large corporations facing litigation for limiting contracts and grant opportunities to applicants from certain groups.

We’re certainly a long way from dealing with simple differences in individual height. And it is here where many battles are being fought. Catholics may differ in their judgments about individual cases. However, all of us must keep in mind a key principle: solidarity. St. Pope John Paul II defines solidarity as “we are all really responsible for all.” Ethicist Matthew Petrusek writes that the principle of solidarity “invites everyone to find concrete ways to help each other succeed,” using examples of recruiting in poor and forgotten places, training programs for those who need greater assistance, and support programs for workers facing particular life challenges.

These are all examples of how businesses and governments supply extra “boxes” to concretize a real preferential option for those in need. But this solidarity cannot be limited to particular groups. Solidarity means we are not first and foremost members of rival and competing groups in a zero-sum struggle over boxes (or spots at Harvard). Instead, it reflects the idea at the heart of the Second Vatican Council’s social vision in Gaudium et Spes (On the Church in the Modern World): God has willed that all people “should constitute one family and treat one another in a spirit of brotherhood,” because we all “are called to one and the same goal, namely God Himself.”

This is the ultimate outcome all Catholics must keep in mind, even as we work to overcome real barriers to the unique vocations of each person along the way.

Read more Salt & Light:

- It takes more than a new stove to save the Earth

- Are your investments morally suspect?

- Only through common seeing can we find the common good

This article also appears in the November 2023 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 88, No. 11, pages 40-41). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Bob Fitch photography archive, ©Stanford University Libraries

Add comment